Notes about the Donders Discussions 2017

29 Oct 2017Donders Discussions is a neuroscience conference organised by doctoral researchers from the Donders Institute. This is the first neuroscience conference I attended as a PhD candidate. The venue - De Hamel, Nijmegen - is a perfect location for such conferences given it’s carefree atmosphere and proximity to a beautiful landscape. It was enriching to sit through sessions about the problems in neuroscience which I do not deal with on a regular basis. I guess it will take time for that information to register in a useful context.

There were 16 sessions (4 sessions running parallely in a group, 4 groups), 4 keynote speeches, and 2 poster sessions over the two days of the conference. I attended some of them and am writing about the interesting bits here.

Keynote speeches

Nael Nadif Kasri

He talked about developing therapy for brain disorders. I am sure this a big sub-field of neuroscience. The best part was about developing neural cultures with particular gene knockouts mirroring the knockouts in particular disorders. The synchronisation of the resulting spiking activity was analysed and they could find distinct activity clusters for the different disorders, as seen in his slide below.

He suggested that by generating targeted therapies for normalising the activity patterns in these cultures, we could develop therapies that could transfer better to humans than from research on mice bred with similar knockouts.

- It would be informative to check if randomly connected spiking neural networks could be manipulated to generate those different spike patterns, in effect pinpointing the neural dynamics or network connectivity parameters that could used to normalise the activity.

Marc Slors

He’s a philosopher who deals with philosophical questions regarding consciousness, free will and the relationship between cognition and culture. He started out by describing the historical shift in perspective about what constitutes cognition (embodied cognition, etc.) It was fun until he claimed that neuroscientists do not account for interactions with the environment while thinking about cognition and its development. That is not true at all. As such, I talked about that with him and it seemed he wasn’t aware of the recent literature which deals with the relationship between cognition and culture (read: effects of language on cognition, etc.) I hope we cannot generalise this to all philosophers. I guess it would have been better if he would’ve focussed on the consciousness and free will parts - parts where I’d say neuroscientists have little or no clue what to do and would appreciate any new perspectives.

Parallel sessions

There were 4 sessions running parallely. I could attend one for each of the 4 groups.

Top-down influences on perception

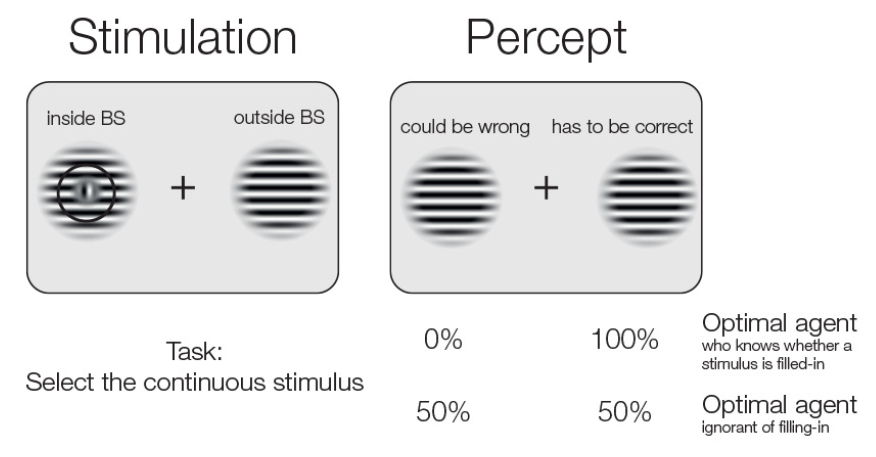

Benedikt Ehinger : Filled-in percepts from the blind spots are judged as more reliable than veridically seen ones

This is a counter-intuitive finding. Subjects were presented with the stimuli shown in the figure below (from his paper), and subjects had to make a forced-choice about which of the two stimuli were more consistent in their orientations.

Why do we trust the information in the blind spot more in this case? His prominent explanation relies on predictive coding. The blind spot is filled in with information consistent with its surroundings. Now even if the surrounding input becomes noisy, the top-down filling won’t be as noisy, so the information received from the blind spot will always match the prediction, thus assigning more weight towards making a decision. This is also supported by their observation that subjects were faster in selecting the blind spot stimuli as opposed to the case where both stimuli were presented outside the blind spot.

- Although the given description might make sense, it is very weird that the brain doesn’t know what it is filling in and what not. I thought this might be an attentional effect. Because the brain might know where the blind spot is, it might have heuristics in place to devote more attentional resources to the area of the blind spot. Benedikt replied that they had performed a saccade experiment with the same stimuli and they found no effect of the blind spot. Yes, spatial attention is shifted before saccades in such cases, but the attentional effect might be independent of eye movements too. This is unclear to me. It nevetheless is an interesting study and I somehow feel such effects might not be reserved exclusively for the blind spot (think inattentional blindness and stuff).

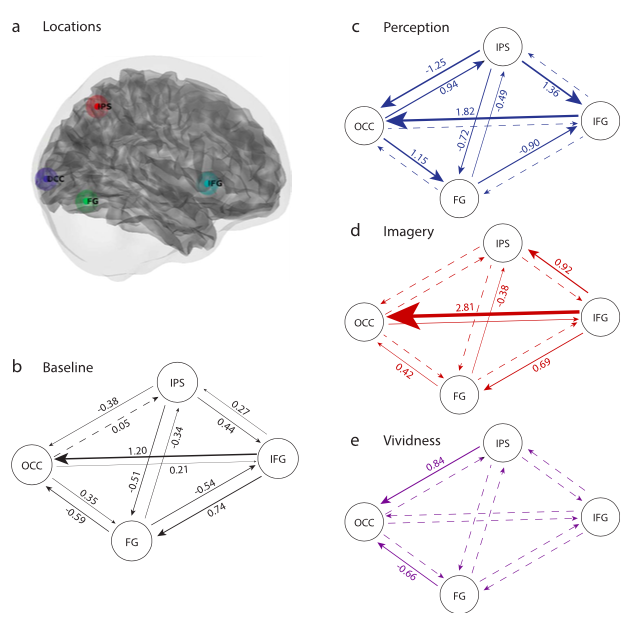

Nadine Dijkstra : Perception as a restricted form of imagery

Using Dynamic casual modelling (DCM), she analysed functional connectivity profiles of four regions of the brain during perception and imagery, showing that both bottom-up and top-down information is involved in perception, and more top-down during imagery, as seen in the figure below (taken from her paper).

These results were expected given previous studies. I think it would be cool to model the same using known anatomical connectivity profiles between these regions. I find it very weird that the inferior frontal gyrus would be connected to the early visual cortex via a direct connection, and even if it is aren’t there other pathways which might be carrying the information reflected in the shown DCM analysis?

Cognitive maps and abstract spaces: the role of spatial neural mechanisms in other cognitive domains

Alexandra Constantinescu : Organizing conceptual knowledge in humans with a gridlike code

Now, I know very little about grid and place cells, so this description might be naive. Grid cells are known to be involved in spatial representation and navigation. Alexandra’s work shows that the hexagonal grid code is not just for the spatial encoding of the environment but might be involved in the representation of any conceptual spaces. In the study, they used images of a stork-like bird whose neck and leg size was manipulated. In this two-dimensional conceptual space, they trained subjects to associate six bird shapes (evenly spread on a hexagon) with symbols so as to make them proficient in the differences. During scanning, they were shown videos of one bird morphing into another which could be thought of as moving along a line in the 2D space. What they found was the fMRI responses in the entorhinal cortex and other regions (similar to the case of spatial navigation) peaked when the movement directions in the 2D space were along the lines joining opposite vertices of some hexagon. This observation suggests that the conceptual space is being mapped with a hexagonal grid-like code!

- I somehow feel this result would be stronger if they had used 4 or any other symmetry in their training stimuli.

- When asked why a hexagonal code would be optimal, I was pointed to Mathias et al., eLife 2016, which alludes to hexagonal close packing being the optimal lattice packing, where lattice packing seems to be compared with packing concepts in a representational space. (I still have to read the paper)

- It would be cool if other such representational spaces could be shown to be mapped by a grid-like code. There was a poster by Simone Viganò (Cortical effects of categorical learning for new words and multisensory objects) which had multisensory stimuli with varying object size and tone pitch, where he tried to answer if assigning categories to these stimuli would change their representation (answer is yes). I still am trying to figure out if the grid formalism could be tested using the fMRI data he already has (obtained from an image 1-back task).

Decision neuroscience

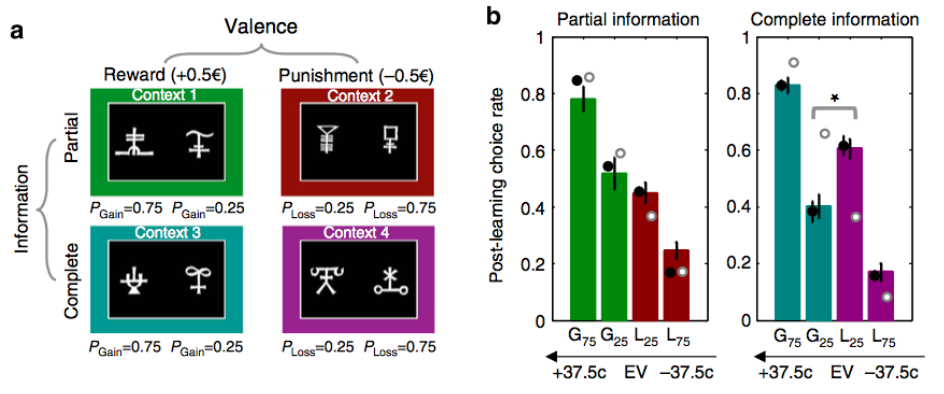

Chih-Chung Ting : Incidental Anxiety enhances reinforcement learning for gains but not for losses

There was a weird, yet intuitive, aspect of human behaviour which was presented as a part of his work. Chih-Chung’s study builds upon the paradigm of Palminteri et al., Nature 2015 (introduces the factor of anxiety), and the relevant results are also seen in that paper. They presented 8 objects to the subjects with different levels of probabilistic punishment or gain, as seen in the figure below (from the paper). Now when two of these stimuli are shown, the subjects had to select one to maximise reward. The partial and complete cases refer to if the subjects were given feedback just about their choice or also about the alternate choice. Depending on these conditions, the subjects show a different response profile after training, as seen in the figure below.

The response during the ‘complete’ condition is weird - the subjects prefer low punishment over low reward! This observation is replicated in Chih-Chung’s findings. They suggest that we are reinforced to choose the low punishment more than we are reinforced to choose low reward. If one thinks about it, if given sufficient time, a rational agent would choose the low reward anytime. These findings reflect an automatic response it seems. This doesn’t seem to happen in the ‘partial’ condition though. (Have to read the paper carefully - maybe they have an explanation).