Arithmetic computations with Spiking Neural Networks

09 Jun 2016This one dates back to 2015. It was a part of my Bachelor’s thesis. But this part has applications beyond the objective of the thesis viz. quadcopter control. We published a paper detailing our method. It is available here (open-access). Note: The description below is a simplistic version of what was done in the paper. All the operations mentioned use well-defined mathematical rules.

Spiking Neural Networks are approximations of biological neural networks. The approximations range from neuron models to synaptic learning models to network topology. The simplest spiking neuron models are the LIF, AEIF, and Izhikevich neurons. They try to capture information about the spike-times, approximate the nature of the action potential, and various operational modes (burst, regular, etc.). An extremely realistic model is the Hodgkin-Huxley model. But it is computationally-intensive, and without access to clusters you cannot simulate a network with hundreds of such neurons. Processes such as dendritic integration and AP back-propagation are unaccounted for in these models. But we have to start somewhere, and we usually start simple. AEIF neurons capture many neural firing modes, and other relevant properties such as spike-frequency adaptation and also encode a refractory function. These are the neurons we use in our method.

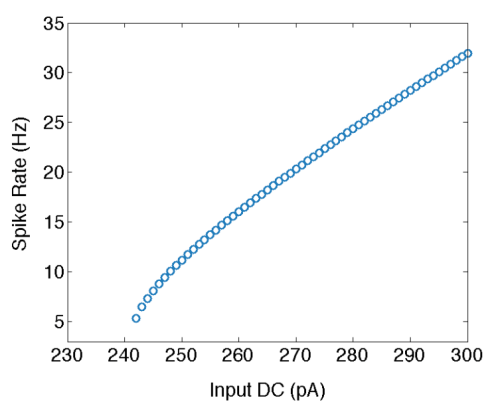

So, the problem was this - how can SNNs implement arithmetic operations such as Addition, Subtraction, Multiplication and Division? This turns out to be a non-trivial question. Spiking neurons have non-linear I-O relationships (logarithmic transfer function), as shown in the following figure.

To implement linear operations such as addition or subtraction, we need to linearise the the transfer function. Now, we focussed on the network influences, rather than trying to manipulate internal dynamics of neurons. To that end, we introduced a self-inhibitory loop that pushed the neuron into the higher current domain in the above figure, which is pretty linear. With a linear transfer function at our disposal, we can do addition and subtraction.

The problem begins with multiplication. I thought about using a recurrent loop with some sort of gated function which would keep adding the same value till we ask to stop it. But then I realised there was a simpler way - use exponentiation and logarithm.

Now, \(\text{A}\times\text{B}=e^{\text{log(A)} + \text{log(B)}}\)

So, if we could construct networks with overall exponential and logarithmic transfer functions, we are done! We not only solve multiplication and division, but we can also create any sort of polynomial transfer function by composing appropriate LOG and EXP blocks!

To implement these LOG and EXP blocks, we turned to adaptive synapses. We designed learning rules that allowed us to generate LOG and EXP responses. Simply put, to generate LOG, the synaptic weight has to decrease with increased pre-synaptic firing rate, and to generate EXP, it has to increase with increasing pre-synaptic firing rate. We then translated these rate based rules into spike-time based rules for performing real-time computations. So, we had EXP and LOG networks, which we composed to implement multiplication and division.

Yes, we know how to use SNNs to implement addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division now. But there were multiple problems with the approach:

- The synaptic adaptation rule was designed and doesn’t seem to be biologically realistic.

- The time required for the networks to stabilise their multiplicative outputs could extend to 0.5 seconds, which make them impossible to use in quick-response control systems such as the quadcopter core control, or biological systems like the cerebellum.

- The operational spike rates lie between 40-140 Hz, which excludes most of the biological neural rates which are pretty low.

So, this is not a biologically realistic model of arithmetic computations, and shouldn’t be treated as such.

A more realistic method of implementing arithmetic operations needs to take into account the actual operational principles of biological neural networks such as tight E-I balance. There are some efforts in this direction. Hopefully, we’ll get to a point where we would be able to converse fluently in neural codes.