Building a simple Reverse Dictionary

06 Nov 2016The associated COLING’16 paper can be accessed on arXiv. Setting a new baseline for phrasal semantics processing. The test dataset and sample code can be found on Github.

Motivation & Idea:

We often can’t find single words to describe our thoughts, but we can describe the concepts in phrases. A Reverse Dictionary (RD) is a solution to this problem. A normal word dictionary maps words to their definitions, but a reverse dictionary maps phrases to semantically-similar words.

This calls for the ability to parse phrases semantically. Now, similarities between words have been studied extensively. These similarities usually rely on a representational space of words, such as word2vec (constructed by crawling a huge corpus and extracting the contextual similarities between words, which also reflects the semantics). There isn’t such a representational formalism, which encodes phrasal semantics, available for phrases. Maybe vectors aren’t suitable for phrasal representations anyway, and we should look towards other mathematical structures, or we should just use sequential parsing while encoding relationships between constituents - as in a RNN.

The methods just mentioned are the logical steps forward. Once we understand how to represent phrasal semantics, linking it to lexical semantics won’t be hard, thus solving the reverse dictionary problem, hopefully. But there are other jugaad that could have simple implementations and could already provide excellent performance for a reverse dictionary. The naivest method is to count to number of words in the input phrase which appear in each word’s definition, and use that as a similarity score from the phrase to every word in the lexicon. As you can tell, this method won’t perform very well.

This approach can be modified to search for lexical relatives of the words in the input phrase and match them with the definitions of the words in the lexicon towards defining a similarity measure. Factors such as frequencies of words (which might distort the similarity measure) appearing in definitions can be taken care of. The word order in the phrase can be factored in by assessing the words’ positions in the constitutent tree of the phrase. Negation words, such as not, can be used as indications to change the constituents following the negation words to their antonyms. All these additions were made by Shaw, R., et.al. in their 2013 model, which performed better than the well-known proprietary software, the Onelook Reverse Dictionary.

Now, I am crazy about neural networks. So, this is what I thought - going from the words in the input phrase to the words in whose definitions they were contained, why should one not carry on from those words to the words in whose definitions they lie in, and so on, building a graph out of the entire lexicon? This Reverse Mapping is the central idea of our approach. It has the intuitive appeal of word meanings converging/composing in a meaningful way onto other words. Of course, for one sensible convergence, there maybe tens of nonsensical covergences. This indeed is a naive approach and we wanted to see how well it could perform (The rationale was - the RD could output tens of words, and all that matters is that the target word be present in there. We could later think of some learning protocol which could selectively enhance connections, something we didn’t get down to).

The Approach:

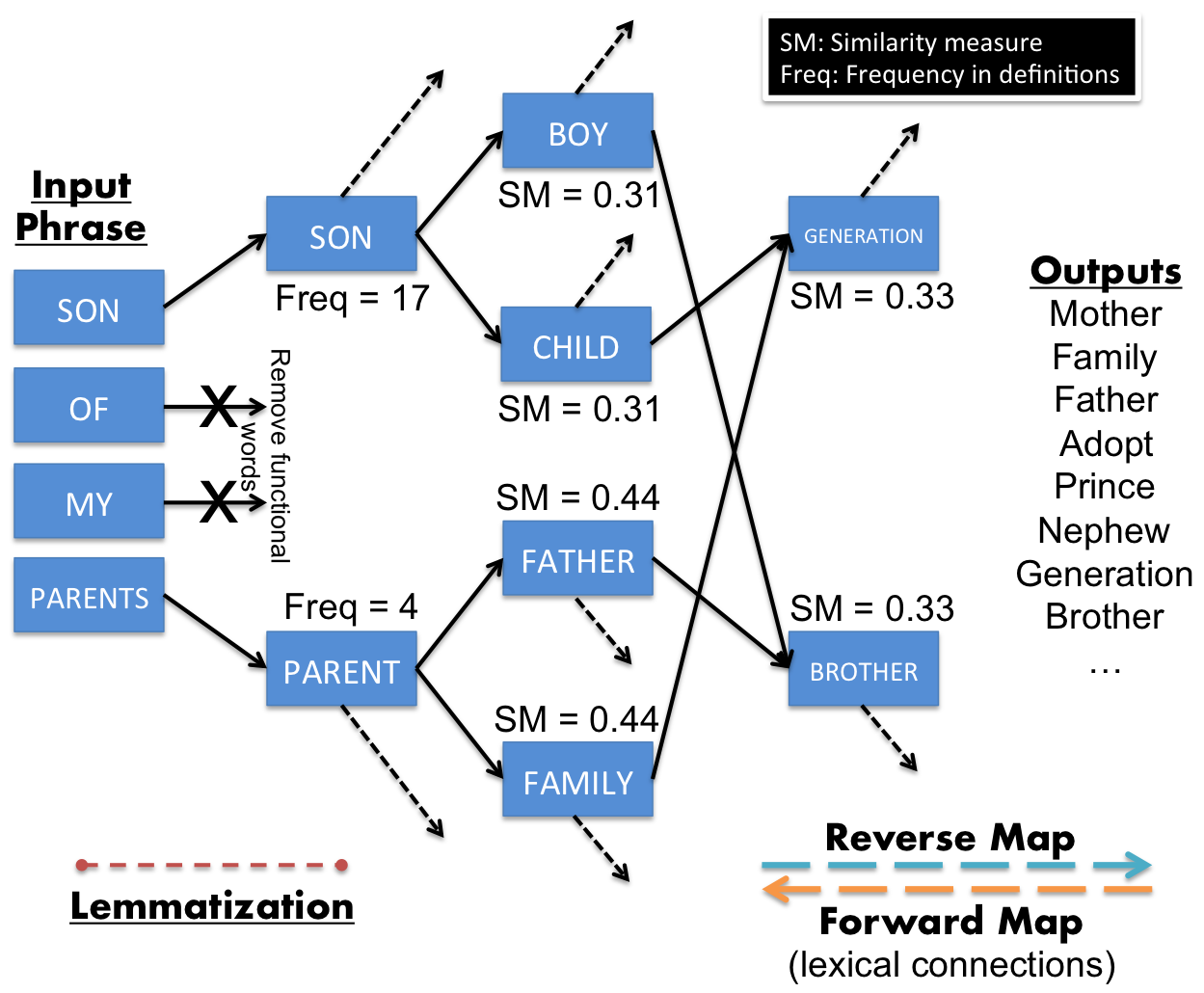

As shown in the figure below,

- Functional/stop words are removed from the input phrase.

- The remaining content words are converted to their base forms using a lemmatiser.

- These input words are activated on the reverse map constructed using one/many dictionaries.

- The graph is evolved until all words are reached by the signals from each input word

- To ensure that all words are connected to every other word, we incorporate forward links (word to words contained in its definition) from the words who do not possess sufficient connectivity. This modified graph’s connectivity is given by the mixed-backlinked-matrix (mBLM), in the paper.

- We thus have a measure of distances between the input words and words in the lexicon. We then deploy the similarity measure to get the similarity between the input phrase and the words in the lexicon.

- The similarity measure E(W,P) of a word W to the input phrase P is given by, \(\text{E}_{W,P} =\frac{\sum_i \left ( \nu_{P_i}\times d_{W,P_i} \right )^{-1}}{\sum_i \nu_{P_i}^{-1}}\), where ν denotes the frequency of appearance in word definitions, and d the distance on the graph.

- All the words in the lexicon are ranked according to their similarity measures, and outputted.

As seen in the figure, the input phrase ‘Son of my parents’ does lead to the word ‘brother’ (the target) as a high-ranked candidate output. As can be seen, the approach is pretty naive, and performs a shallow extraction of useful semantics. Let’s see anyway how it compares to the state-of-the-art approaches.

Testing procedure:

On the lines of Hill, F., et.al., we decided to create a dataset of user-generated phrases given target words. We had to create a new database as we were using a smaller lexicon (3k words) for the first phase of our project. 25 users generated 179 phrases for us. The performance of a reverse dictionary is given by the rank of the target word in its outputs, given an input phrase. We also extracted definitions for those 179 target words from the Macmillian word dictionary - which we did not use in building out graph.

Results and Conclusions:

For the user-generated phrases, our best model could find the target word in 10% (top-10 outputs), and 53% (top-100 outputs) of the cases, as opposed to 7% (top-10 outputs), and 52% (top-100 outputs) for Onelook. For the Macmillian word definitions, our best model could find the target word in 25% (top-10 outputs), and 84% (top-100 outputs) of the cases, as opposed to 20% (top-10 outputs), and 68% (top-100 outputs) for Onelook. If we were to generate a random selection of words, we could find the target word in 0.01% (top-10 outputs), and 3% (top-100 outputs) of the cases. So, our approach is actually performing well (sanity-check).

So, our approach performed atleast as well as the Onelook Reverse Dictionary on the 179 user-generated phrases and Macmillian word definitions. We also compared our approach with Onelook on the 200 phrases provided by Hill, F., et.al., and our approach performed atleast as well. Now, the RNN-based approach used by Hill, F., et.al. performed only slightly better than Onelook. This implies that the semantics being processed by the RNNs are pretty shallow (as the performance is comparable to our naive approach).

Our approach doesn’t scale well to a bigger lexicon, as seen in the paper. It nevertheless is a cheap way of converting any dictionary into a reverse dictionary. Our method, and that of Shaw, R., et.al, could be treated as baselines in the sense that we know how shallow the semantic processing is. The way forward, of course, are RNNs and other semi/un-supervised architectures, which could extract their own features, and which could settle on novel mathematical structures. The performance baselines provided in our paper could be used as a sanity-check for deep semantic processing in the newer architectures.

Acknowledgement:

The “we” here - Varad Choudhari and me. He took care of all the computational heavylifting. Kudos to him!

I would like to thank Ionut-Teodor Sorodoc, Arpan Saha, Julie Lee, and Prof. Roberto Zamparelli for making useful comments about the project, and the 25 participants who generated the phrases.